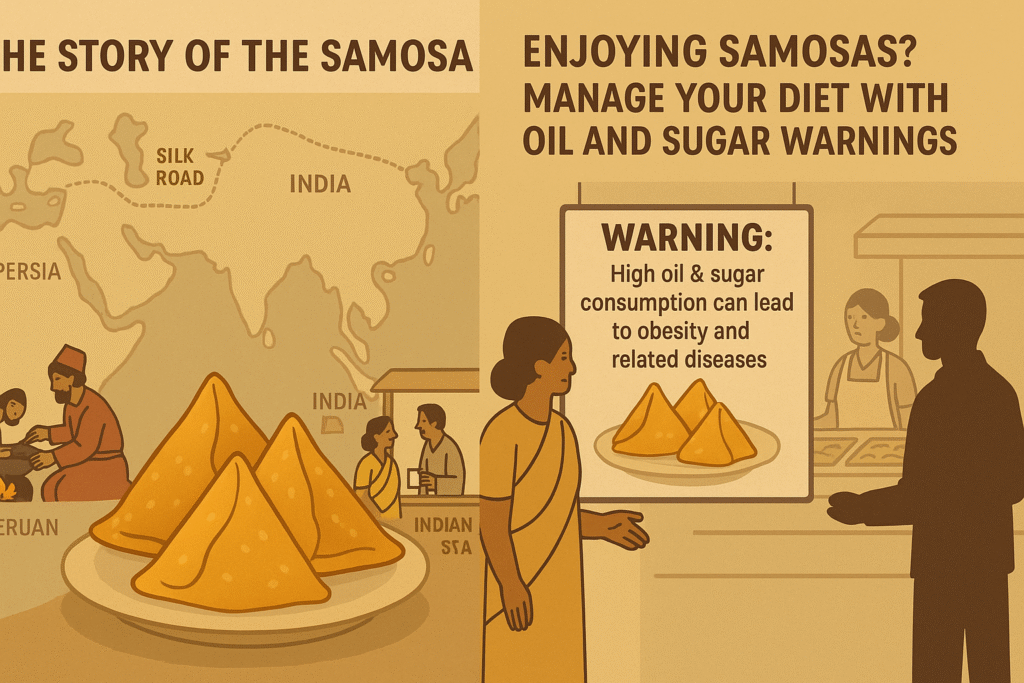

Recently an advisory by the Indian government created a flutter in newsrooms and on social media. It was about a directive to the canteens in government institutions to display health warning about the negative effects of oil and sugar. This came against the backdrop of Reports that by 2050, obesity is likely to become a national health concern in India.

The government wanted canteens selling snacks such as samosas and jalebis to display this warning. Some over-enthusiastic news-writers made it to appear that the government has directed that samosas and jalebis be labelled with such warning.

Comparison with cigarette warning came in lighter vein in news reports. And even in the case of cigarettes, the warning is not printed on each cigarette but on its packets. Similarly, the health warning was to appear somewhere in canteens, most likely on their walls. But it was never about putting such labels on samosas. The government got another opportunity to declare that news-writers are fools. The PIB picked one such report by a once-reputed news outlets to call it “fake news”. Labelling requirement was definitely fake news but warning as health advisory was not.

Reports emerged from canteens and circled back to the government, which used them to its advantage. But the whole episode gave samosa much newsroom publicity that it never needed This, however, gives us an excuse to tell the story of your favourite snacks.

The modest samosa: a delectable golden pyramid that has claimed pride of place in the hearts of millions. To bite into its crisp pastry, unearthing the warmly spiced filling within, is to participate in a story that traverses centuries, continents, and empires—a tale as layered and surprising as the snack itself.

Yet, beneath its ubiquitous crust, the samosa holds a history that is every bit as rich as its savoury core.

Ancient beginnings: Across the Silk Roads

Few today appreciate that the samosa’s earliest home was not the crowded alleyways or bustling railway platforms of India, but the palatial kitchens and caravan camps of ancient Persia and Central Asia. Around the 10th century, the triangular pastry was celebrated as sanbosag, sambusak, or sambusaj in Persian and Arabic—a portable treat crammed with minced meat, onions, and nuts, seasoned with fragrant spices from the Silk Roads. Persian historian Abul-Fazl Beyhaqi wrote with relish about royal banquets in the Ghaznavid court where these pastries graced the tables, their popularity owing much to a clever marriage of taste and convenience.

The adaptability of the samosa—flavourful, easily packed, and resistant to spoilage—meant it nourished both weary travellers and palace dwellers alike. Arab cookbooks from the 13th century detail these pastries filled with everything from spiced lamb to sweet nuts, hinting at a tradition of endless variation long before India fell under their spell.

Crossing into India: Courtly intrigue and culinary change

The samosa found its passage to the Indian subcontinent in the 13th and 14th centuries, carried on waves of trade, conquest, and cultural exchange that shaped the Delhi Sultanate. Persianate tastes dominated royal tables, and the poet Amir Khusro himself remarked on courtly gatherings where dainty sambusaks accompanied poetry and intrigue.

The famed traveller Ibn Battuta, remarking on the decadent delights of Delhi, recorded the presence of mince-filled triangles, fried or baked until golden—a dish designed to awaken the palate in anticipation of richer fare.

Within Indian kitchens, the samosa underwent a remarkable metamorphosis. Scarcity of meat in some regions and the influence of elaborate vegetarian cuisines prompted local cooks to experiment.

When the humble potato arrived from the Americas via Portuguese traders in the 16th century, it provided new possibilities. By the dawn of the 19th century, the classic north Indian samosa had emerged: spiced potato and peas, enlivened with chilli, cumin, and ginger, wrapped in crisp pastry.

From aristocracy to the everyman

The story of the samosa in India is charmingly egalitarian. No longer confined to the tables of sultans and nobles, by the colonial era, it had become the essential railway snack, sold fresh and piping hot to second-class travellers and titled civil servants alike.

Tea-shop stalls, railway platforms, and monsoon gatherings pulsated with the sound of oil sizzling, the golden triangles eagerly wrapped in yesterday’s news.

Anecdotal lore abounds: samosas have been served at secret meetings during India’s fight for independence, and at roadside tea stalls where the fates of cricket matches and elections are endlessly debated.

Indian independence leaders, including Gandhi, were known to serve vegetarian fare—sometimes with samosas—at humble political gatherings, transforming the snack into a subtle symbol of unity and shared ambition.

Over the decades, each region put its own spin on the snack. In the east, Bengali shingaras arrived lighter, perhaps stuffed with cauliflower and peanuts. In Gujarat, miniature samosas appeared, sometimes filled with sweet coconut; in the south, onions and curry leaves dominated.

Meanwhile, in Goa and Hyderabad, samosas returned to their meat-filled origins, reflecting a glorious blend of Islamic and local influences.

Beyond borders: Migration and modernity

As the Indian diaspora spread, so did the samosa—now embraced in Britain, Kenya, and the Gulf, adapted to every new land and occasion. In the UK, it became an indispensable staple of the British-Indian tea table; along the Swahili Coast of Africa, it is a Ramadan treat, itself a product of centuries of Indian migration and cultural melding.

Modernity has only deepened the samosa’s mystique. Today, gourmet food trucks, “rainy day” samosa hashtags, and even a 2016 samosa vending machine in Delhi reflect a snack adroit at surviving—and thriving—in the age of instant gratification and social media clamour.

Bollywood immortalises samosa-fuelled friendships; political cartoons lampoon leaders holding forth over chai and savouries. The samosa, by now, is a “great leveler,” devoured by rickshaw drivers and business magnates alike.

Flavours of identity

The samosa remains a canvas for regional ingenuity and shared history:

- North India: Large, robust parcels bulging with spicy potato and peas, sometimes studded with nuts or raisins.

- West India: Gujarati singaras, dainty with coconut or sweet peas.

- East India: Bengali shingaras, light and crisp, occasionally filled with groundnuts or winter vegetables.

- South India: Savoury triangles redolent of onions and curry leaves, sometimes enclosed in thinner pastry.

- Goa and Hyderabad: Meat, particularly mutton or chicken, makes a triumphant return—an echo of the samosa’s Persian past.

How much oil or fat is in a samosa?

While the samosa delights the palate, it is hardly a lightweight where oil or fat content is concerned. A standard deep-fried samosa—roughly 100 grams, typical of North Indian street vendors—can contain between 12 and 20 grams of fat, depending on the recipe and frying method.

Much of this comes from the pastry, which absorbs oil during frying, as well as from any ghee or butter used in making the dough.

It is worth noting that home-baked or air-fried samosas will contain significantly less fat, but the traditional version remains an indulgence, best savoured in moderation—a small price to pay, perhaps, for so much history in a single bite.

Enjoying samosas? Manage your diet with oil and sugar warnings

As governments warn of the risks associated with high oil and sugar consumption—chief contributors to obesity and related diseases—how does the samosa lover navigate these realities without sacrificing cultural and culinary joy?

1. Understand what’s at stake

The classic deep-fried samosa, as explored in the story above, is a celebration of taste and history—but also packs a significant amount of oil, with a typical piece containing 12–20 grams of fat. Regularly eating such fried, fatty snacks can contribute to excessive calorie intake and elevate the risk of weight gain and associated illnesses.

Similar advice applies to sweets often served alongside or after snacks; added sugars can quickly exceed healthy limits and compound the effects of a high-fat diet.

2. Practical tips for samosa lovers

- Savour, don’t splurge: Treat samosas as an occasional delicacy rather than a daily staple. Limit portion size: enjoy one samosa at a time, and fill the rest of your plate with fresh vegetables, fruits, or lean proteins. Share samosas at gatherings to spread both joy and calories.

- Choose healthier preparation methods: Opt for baked or air-fried samosas at home, which can dramatically reduce fat content. Drain well and blot excess oil if buying fried samosas from outside.

- Balance your plate: Enjoy samosas as part of a meal, not as a meal itself. Pair with fibre-rich salads or yoghurt-based dips instead of sugary drinks or more fried treats.

- Mind the sweets: Watch your total sugar intake through the day; if you know you’ll be having a sweet or a sugary chutney with your samosa, cut back on sugar elsewhere.

- Stay active: Regular exercise and maintaining an active routine can help offset the occasional indulgence.

3. A sample day for the samosa enthusiast

| Occasion | Smart samosa strategy |

|---|---|

| Breakfast | Skip oily/fried snacks; have whole grains and fruit |

| Lunch | Enjoy a samosa (preferably baked) with lentil soup and salad |

| Snack | Opt for fresh fruit or nuts, or share a samosa with a friend and skip other fried foods |

| Dinner | Keep it light: grilled veggies, lean protein, and whole grains |

| Dessert | If you had a samosa earlier, skip the sweets or have just a bite |

4. Take home from samosas

- Samosas are best enjoyed occasionally and in moderation—think of them as a flavourful chapter in your food story, not the whole book.

- Balance indulgences with nutrient-dense foods, mindful portions, and regular activity.

- Explore home-made or baked options to reduce oil and calorie content.

- Listen to government health advisories, but allow yourself the joy of tradition on special occasions.

By integrating these habits, you can relish the historical and culinary pleasure of the samosa—without letting it weigh too heavily on your health.

Sources: World Health Organization; Indian Council of Medical Research “Dietary Guidelines for Indians 2020”; nutritional panels of street samosas.

A bite of history

The tale of the samosa is a testament to migration, adaptation, and cultural exchange. From Persian courts and Central Asian camps to the lanes of Mumbai and Dhaka, the samosa is more than a snack: it is a chronicle of civilisations rubbing shoulders and palates colliding across centuries.

In its journey from sanbosag to shingara, it has moved from royal delicacy to street food icon—each bite still hinting at the trades, tastes, and stories of centuries past.

With every golden triangle, we taste a shard of history: ancient ingenuity, colonial improvisations, and an enduring flair for reinvention.

The samosa’s journey—layered, surprising, utterly moreish—is a salute to the ordinary made extraordinary, and a reminder that the simplest of foods can tell some of the world’s grandest stories.

References

- Scholarly works on Persian and Indian cuisine history

- Ibn Battuta’s travelogues; medieval Persian culinary manuscripts

- Writings of Amir Khusro; Indian court chronicles