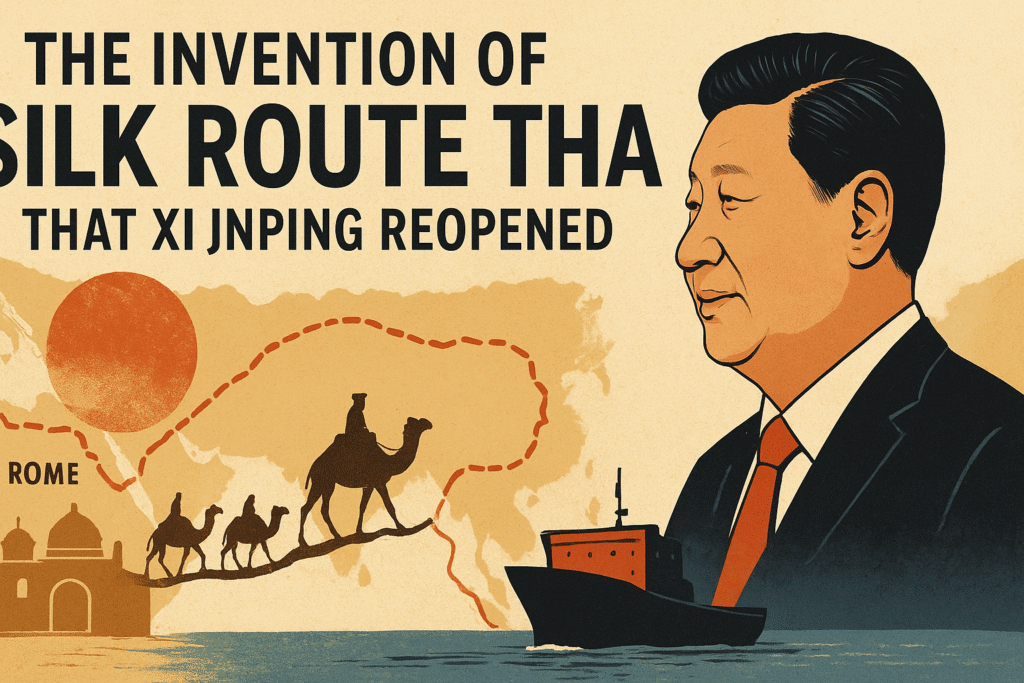

In speeches, museum plaques, school textbooks, and—most recently—geopolitical doctrine, the Silk Road is presented as an ancient superhighway that once stitched together China, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe in a seamless chain of overland commerce. This imagined route, we are told, carried caravans of silk, spices, knowledge, and ideas across continents, forging civilizational links that Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) now seeks to revive.

The only problem: the Silk Road as a single, unified route never existed.

The 19th-Century Birth of a Supposedly “Ancient” Route

The term “Silk Road” (Seidenstrasse) was not coined by ancient Chinese, Central Asians, Arabs, or Romans. It was coined in 1877 by the Prussian geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen in his book China. Richthofen was attempting to map ancient trade patterns for European scholarship and needed an evocative label. The phrase was a tidy metaphor, not a historical term.

Even more revealing: the phrase only entered English in 1938, when the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin published The Silk Road. From there it slowly seeped into popular imagination, eventually taking on a life of its own—far removed from the uneven, fragmented reality of ancient Eurasian exchange.

Thus, a 19th-century scholarly invention became a 20th-century global myth.

No Single Road, No Continuous Route

The real historical landscape was a patchwork of regional networks, constantly shifting according to political stability, climate, war, and geography. Empires rose and fell, nomadic groups controlled passes, and routes changed with every generation. There was no single artery connecting Chang’an to Rome.

Even more inconvenient for the popular narrative: China and Rome barely had any direct contact.

- Chinese chronicles record only a handful of Roman envoys, many of which likely came via intermediaries or were misidentified merchants.

- Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder complain bitterly about the “oriental luxuries” draining Roman gold—but never suggest Roman merchants reached China.

The two empires knew of each other. They did not trade directly.

The Case of the Roman Coins: India, Not China

If Rome and China were bound by a flourishing overland Silk Road, the archaeological record would show it. Instead, it shows the opposite:

- Thousands of Roman gold and silver coins have been excavated from southern India, especially Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

- In China, such Roman coins are rare to the point of near nonexistence.

Why? Because goods did not move from China to Rome across deserts and mountains. They moved by sea, along a predictable, seasonal maritime highway driven by monsoon winds.

The Indian subcontinent—particularly its western and southern ports—was the great connector. Chinese silk traveled to India via Southeast Asian maritime routes. From India, it traveled to Arabia and the Red Sea, where Roman merchants purchased it.

This was the real engine of Afro-Eurasian exchange: the Indian Ocean world, not an overland Silk Road.

India’s Central Role in the Ancient Global Economy

For centuries, India was the commercial hub of the known world.

Its ports—Arikamedu, Muziris, Barygaza, Sopara—were buzzing cosmopolitan centers linked to Africa, Arabia, Persia, Southeast Asia, and the Mediterranean. Arab navigators, Tamil sailors, Roman merchants, and East African traders created a shared commercial space that facilitated the exchange not only of goods but of ideas, religions, and technologies.

The lion’s share of goods that Rome imported from the East—pepper, ivory, gems, textiles—came directly from India. Silk from China arrived not through Central Asia but through Indian maritime intermediaries.

In other words: India was the fulcrum. The Indian Ocean was the highway. The Silk Road was a later fantasy.

How Modern China Revived a 19th-Century Myth

If the Silk Road was invented in 1877, why is it everywhere today?

The answer lies in geopolitics. Xi Jinping recognized the power of myth and repurposed it. In 2013, when he launched the Belt and Road Initiative in Kazakhstan, he framed it as the “rejuvenation” of the ancient Silk Road.

This narrative achieves several goals:

- Historical legitimacy — By claiming continuity from a glorious ancient route, China positions BRI as a natural heir to history.

- Soft power — The Silk Road brand evokes romance, mutual exchange, civilizational harmony.

- Geostrategic cover — Under the cultural veneer, BRI projects infrastructure, influence, and leverage across Asia, Africa, and Europe.

The brilliance—and risk—of this strategy is that it weaponizes nostalgia. It asks nations to buy into a shared historical memory that never existed.

The Problem With Myth-Based Geopolitics

Myths can inspire. They can also distort.

The oversimplified Silk Road narrative marginalizes the historical importance of maritime Asia, the cultural richness of Indian Ocean trade, and the centrality of the Indian subcontinent in global commerce. It subtly reframes Eurasia as a space where China was always the initiator, organizer, and center.

Yet history tells a different story: India—not China—was the great middleman of the East-West economy, and the seas—not deserts—carried the world’s wealth.

Why the Myth Matters Today

The Silk Road is a reminder that history is not just about the past. It is a resource that states deploy in the present. Xi Jinping’s “reopening” of the Silk Road is less a revival than a reinterpretation—an attempt to root contemporary geopolitical ambitions in an invented antiquity.

Understanding the real history helps us understand modern power. It also helps reclaim the narrative for those whose histories were overshadowed by a myth: the sailors of the Indian Ocean, the merchants of India, Arabia, and Africa, and the countless unnamed intermediaries whose lives truly shaped the world’s first globalized economy.

The Silk Road may be a beautiful story. But the truth is even more compelling.