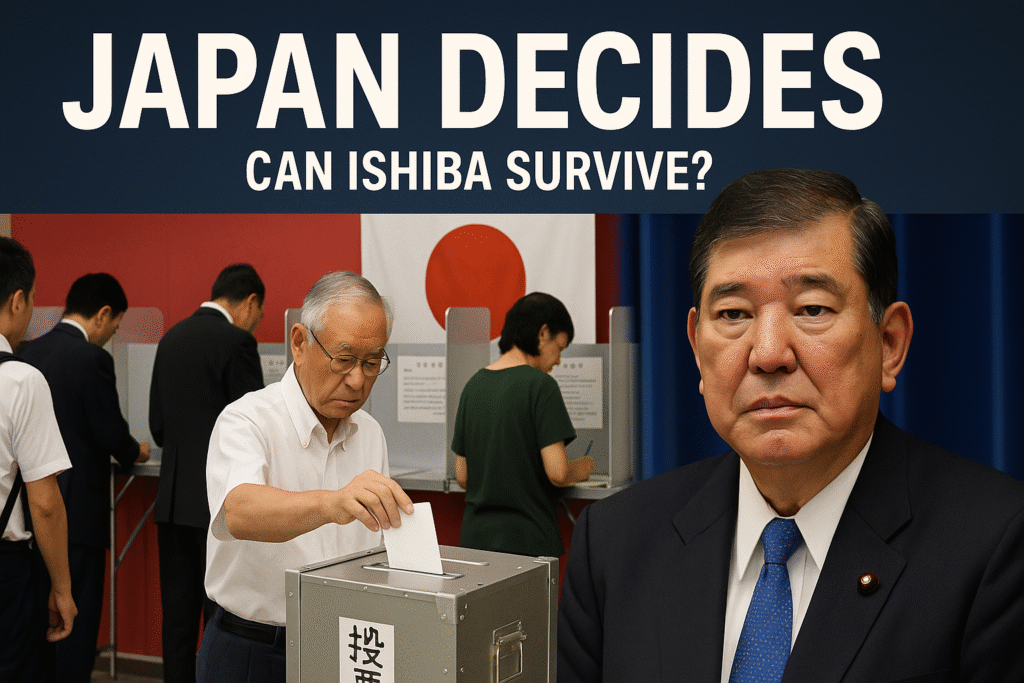

Japan is witnessing political drama unfold in real time as voters cast their ballots in the Upper House election—the Senate poll that could reshape national politics and future leadership. This isn’t just another trip to the polling booth.

For Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, whose Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has been the controlling force in Japanese politics for decades, it’s a day of reckoning. The numbers are stark and the stakes, immense.

When numbers become fate

Of the 248 seats in the House of Councillors, 124 are up for election today. To keep a firm grip on power, the LDP and its coalition partner, Komeito, need to secure at least 50 seats. However, the latest polling (Asahi Shimbun, 13-14 July) projects they may only manage around 43—putting them a worrying seven seats short of a majority. That’s not merely a poor result; it’s an open invitation for opposition parties to demand change at the top and force a rethink of government priorities.

The primary reasons behind this surge of discontent? Inflation and immigration. Voters are feeling the pinch as the cost of everyday life—especially essentials like rice—soars. Many are questioning whether government cash handouts can provide meaningful relief, while opposition groups promise bolder solutions, such as tax cuts and increased state support. At the same time, Japan’s changing demographics and a rapid increase in foreign workers have made immigration a fiercely debated topic, with parties like the right-wing Sanseito seizing the opportunity to push for stricter laws and riding this wave toward a possible tripling of their representation, up to 18 seats.

Why Prime Minister Ishiba’s career is on the line

This is not just a test of party support—it’s a referendum on Ishiba’s leadership. He has only held office for 10 months after the LDP lost its outright lower house majority in a snap election and subsequently formed a minority government. Ishiba’s approval ratings have tumbled, not only because of economic malaise but also due to a scandal involving gift vouchers and the perception of policy drift. With rivals inside his own party circling, and opposition parties uniting to force a change, Ishiba’s future hangs by a thread.

If the coalition cannot cross the 50-seat barrier:

- It would be seen as a public vote of no confidence in Ishiba.

- He could be forced to resign, or end up having to strike difficult bargains with parties previously in opposition—potentially giving up ground on key policies or appointments.

- Political and economic instability could ripple outwards, with markets jolted by a 10-year government bond yield topping 1.595%—a level unseen since 2008—as investors worry over the outlook for Japan’s fourth-largest economy.

The timing further complicates the picture. With ongoing trade negotiations with the United States and a critical 1 August deadline for a new agreement looming, instability in Tokyo could undercut Japan’s bargaining position and strategic interests.

So, how did Japan get here? A guide to its political system

Understanding why today’s election matters means knowing how Japan’s system functions:

A constitutional monarchy

- The Emperor is the country’s symbolic figurehead, representing national unity without any direct political power. All actual authority is held by elected officials.

- The Prime Minister is the head of government, chosen by the Diet (parliament) and responsible for leading both the Cabinet and national policymaking.

The National Diet: Japan’s parliament

| House | Seats | Role | Term | Current Heat (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| House of Representatives | 465 | Chooses PM, passes budget, most influential | 4 years | LDP lost majority in 2024 |

| House of Councillors | 248 (124 up for election) | Reviews laws, can delay lower house decisions | 6 years (half every 3) | Ruling coalition’s grasp at risk |

Lawmaking and everyday governance start and end in the Diet. The upper house—whose election is now underway—has the power to delay and scrutinise decisions, sometimes creating “twisted Diets” when different parties control each chamber, leading to political deadlock.

The main parties on the Japanese stage

| Party Name | Leader | Ideology | House of Reps | House of Councillors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) | Shigeru Ishiba | Conservatism, nationalism | 191 | 115 |

| Komeito | Tetsuo Saito | Social conservatism, Buddhism | 24 | 27 |

| Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) | Yoshihiko Noda | Social liberalism | 148 | 38 |

| Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) | Hirofumi Yoshimura, Seiji Maehara | Right-wing populism | 38 | 20 |

| Democratic Party for the People | Yuichiro Tamaki | Conservatism | 28 | 10 |

| Japanese Communist Party (JCP) | Tomoko Tamura | Progressivism | 8 | 11 |

| Reiwa Shinsengumi | Tarō Yamamoto | Left-wing populism | 9 | 5 |

| Sanseitō | Sohei Kamiya | Ultranationalism | 3 | 1 |

The LDP’s dominance once seemed unshakeable, but coalition politics and an energised opposition mean compromise is now the rule. Today, parties like Ishin and Sanseito are gaining ground as voters search for answers to everyday challenges.

Elections and participation

- House of Councillors elections take place every three years, with half the seats up for grabs. Representatives serve six-year terms.

- Almost 21.5 million early votes were cast in this cycle—a record—demonstrating both public engagement and high stakes.

- Voting is open to all Japanese citizens aged 18 or above, reflecting the country’s commitment to universal suffrage.

Coalitions, bureaucrats, and the emperor

Coalitions are now the norm rather than the exception. Japan’s powerful bureaucracy often shapes policy behind the scenes, while the emperor’s role is strictly ceremonial—a living embodiment of continuity, but with no influence over decisions or government direction.

Why this election matters for every Japanese citizen

Today’s Senate vote is more than a contest of parties and personalities. It is a mirror of Japanese anxieties: about the future, about change, and about the need for leadership that can deliver real solutions. If the LDP and Komeito do stumble—failing to cross the magic number of 50—Japan’s political world could look very different tomorrow, and Shigeru Ishiba may become the first casualty, replaced or forced into painful deals that alter the direction of Japanese policy.

For observers at home and abroad, this is a rare chance to see the mechanics and meaning of Japanese democracy at close quarters—where every seat counts, and the future of leadership is truly on the line.

With the results of the Upper House vote expected soon, all eyes are on Japan—not just to learn who wins or loses, but to understand how one of the world’s oldest democracies navigates its most pressing modern challenges. Stay tuned: the story is far from over.