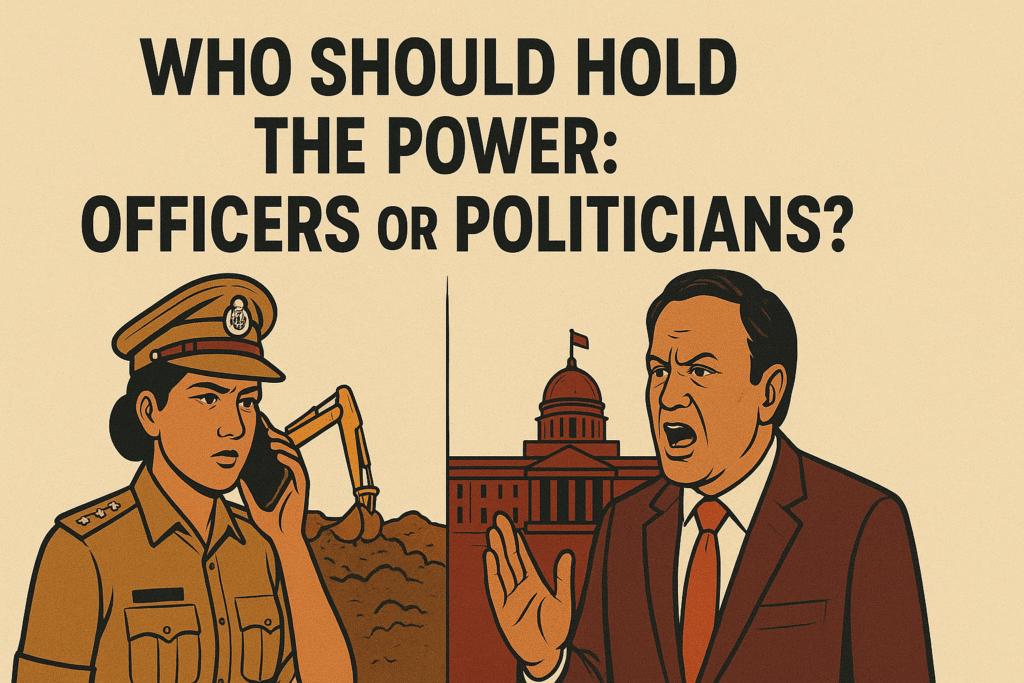

Many Indians saw videos of what really happened in Solapur, Maharashtra this week. A striking confrontation unfolded in Maharashtra’s Solapur district, throwing into sharp relief the fault lines between merit-driven professionalism and the realities of Indian politics.

When IPS officer Anjana Krishna led a crackdown on illegal excavation, she found herself on an unexpected call with Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar. Unrecognised by Krishna, Pawar loudly asserted his authority, asked her to halt the operation, and rebuked her for not knowing who he was on hearing his voice over the phone, the device belonging to one of his aides, the officer oblivious to the connection between the two — actions widely captured and debated nationwide.

The episode swiftly became a symbol: politicians claiming power, public servants defending process.

If you haven’t watched those videos, here are two widely circulated clips:

Who Should Hold the Power: Officers or Politicians?

For officers like Krishna, every step up is earned—not through name or popularity, but through deep study and hard work. The UPSC selection process for civil servants requires passing preliminary and main examinations, followed by interviews, years of probation, and continual scrutiny throughout one’s career—ensuring social commitment and technical competence.

In contrast, political ascent often results from popular appeal, social lineage, or constituency management. Too rarely does it demand more than the gift of persuasion and a network of patrons. The politicians too spend many years in public life before they feel they have arrived, except for those who inherit politics. Ajit Pawar is a mix of both.

But what happened in Solapur is not an isolated case. Recently, an audio clip was circulated over social media showed a Bihar politician threatening an official serving tier-three of India’s democratic structure. For various reasons and factors, the tone, tenour and the choice of words used by the Bihar official were markedly different from those of Krishna, who is a Thiruvananthapuram-born 2022-batch IPS officer.

The Bihar official was nonchalant about the threats that the local legislator gave to him. He, in fact, dared the politician to do whatever he wanted, saying he wasn’t afraid of being transferred to some other (dreaded) place. Later, apparently fearing for his life, the young government servant filed an FIR with the police under sections that included caste-based harassment or civil rights provisions of the law.

On the other hand, Anjana Krishna sought a written instruction on her phone to ensure that the speaker was the same person what he claimed to be. Must note, it would have been a blemish on her career had she believed such a voice and the person turned out to be an imposter. She would any have invited the ire, if not wrath, of the man holding the constitutional office of a high-ranking minister in one of the biggest and richest states of the world’s largest democracy.

We have also seen in the past politicians, ill-literate or ill-educated included, making high-ranking officials serve them in the manner we read in the stories depicting the feudal past of India. Meritocrat officers have been seen polishing shoes, bringing spittoons or hunting for buffalo or jackfruit grown on the lawn of the official residence of the public representatives.

Is India Ignoring Its True Talent Pool?

Think about it: India’s officers clear some of the world’s most challenging exams, demonstrating not just knowledge but resilience and integrity. Shouldn’t the same be demanded of those with even greater authority — the power to set policy and allocate resources?

If the system tested political leaders as stringently as it selects officers, governance would naturally favour expertise over expediency, planning over populism.

Should Politicians Prove Their Merit Too?

Isn’t it time for political parties to raise the bar for future candidates? India’s parties could introduce rigorous internal selection protocols, requiring minimum qualifications, records of public service, or policy expertise.

Such reforms would not suppress democracy, but would enrich it — ensuring voters can choose from the best and brightest, not merely the loudest or the most familiar.

How Can Voters Demand Real Accountability?

At its heart, the Solapur incident is about accountability. Does India reward charisma and lineage, or real achievement?

Voters have the power to redefine what it means to deserve office, demanding that parties and politicians meet the standards their officers do — disciplined, informed, and proven.

Last Word: Meritocracy is Democracy’s Best Defence

Political influence without merit weakens institutions and public trust. India is at a crossroads: will it embrace leaders tested for their abilities, or continue to risk policy at the whim of unprepared power?

If the ballot box demanded more than just popularity — if a record of achievement and integrity was required — every citizen would benefit.

The message from Solapur is clear. As a nation, India must build a system where leaders, just like officers, earn their stripes through merit — not through inherited privilege or cacophonous fanfare.

One possible example could Anjana Krishna’s home Thiruvananthapuram itself, where voters have been electing a former United Nations top official (Shashi Tharoor) as their voice in India’s Parliament.