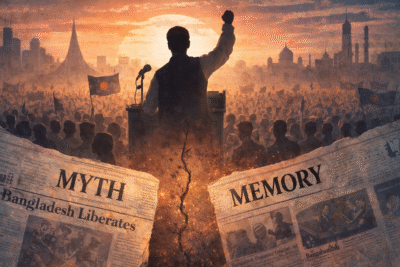

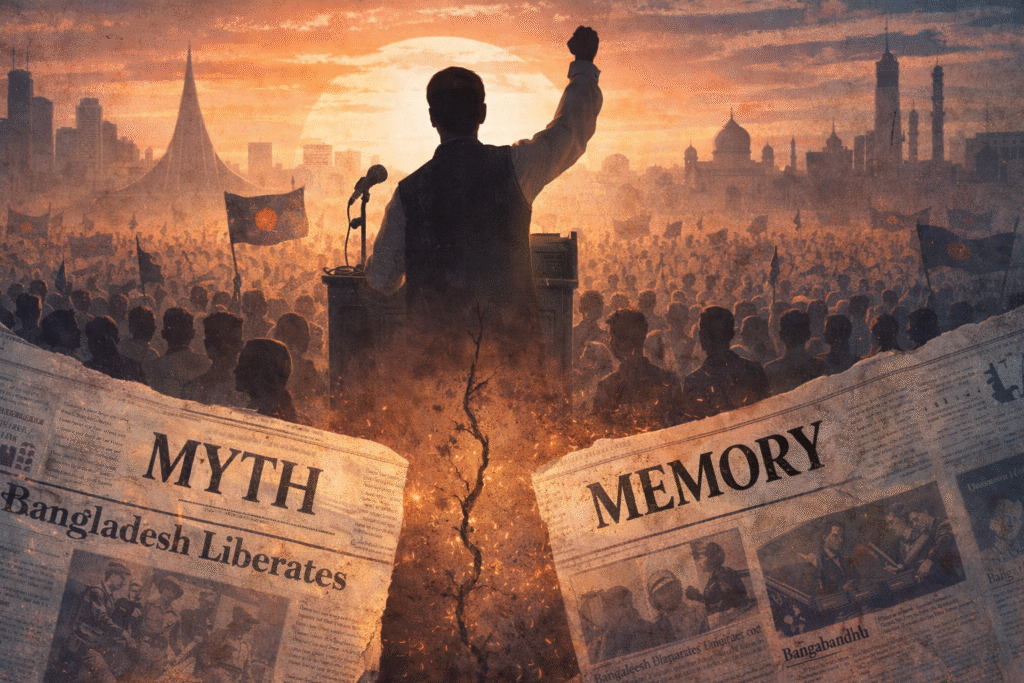

For half a century, Bangladesh has treated Sheikh Mujibur Rahman not merely as a political leader but as something rarer in modern politics — a moral origin story.

He is Bangabandhu, the friend of Bengal, the voice of the liberation war, the man whose 7 March 1971 speech became a prelude to statehood. Yet the endurance of that national myth is precisely why his legacy periodically returns to political contention. Nations do not argue about obscure leaders; they argue about founders.

A recent re-examination appears in Inshallah Bangladesh by journalists Deep Halder, Jaideep Mazumder and Shahidul Hasan Khokon. The book does not try to demolish Mujib’s stature outright. Instead, it attempts something more uncomfortable: separating the historical politician from the sanctified national memory.

Its core suggestion is simple but explosive — the Mujib remembered in national narratives was not the Mujib who began his political life.

Before 1971: A student activist in a communal age

The authors begin not in Dhaka in 1971 but in Calcutta in August 1946. The city was then convulsed by the Direct Action Day riots, later called the Great Calcutta Killings, which preceded Partition by a year.

Drawing on historical accounts, they describe the young Mujib as a Muslim League student activist associated with Bengal premier Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. According to the book, he helped mobilise political demonstrations, raised League flags and joined confrontations in the charged environment of the time.

They quote accounts that student activists “would be instrumental in the start of Direct Action Day’s violence,” while recounting Mujib’s own recollection of shouting slogans and throwing stones during clashes. Importantly, the authors do not accuse him of organising massacres; rather, they place him within the communal mass politics that dominated late colonial Bengal.

The point is interpretive. Mujib, they argue, did not emerge as a secular nationalist hero at the outset. He was a product of the same turbulent political culture that produced leaders across South Asia on the eve of Partition.

This matters because Bangladesh’s official narrative tends to begin in 1971. The book pushes the timeline backwards.

The transformation

The authors acknowledge a political evolution. After the creation of Pakistan, Mujib gradually broke from the communal framework of the Muslim League and embraced linguistic nationalism, championing Bengali identity over religious identity. Over time, he articulated the idea of a plural Bangladesh — what he famously described as Sonar Bangla, a homeland belonging to all citizens regardless of faith.

In the book’s words, he evolved into “a secular political being”, a shift tied to his belief that communal politics hindered democracy and social progress.

It is not that Mujib remained a communal politician; it is that he changed. The question raised is whether the national narrative recognises that evolution — or erases it.

After independence: Contradictions of power

The authors’ sharpest critique concerns the period after independence in 1971. They present a series of contradictions between Mujib’s image as a secular democratic founder and some of his policies in office.

They point out that although Bangladesh was founded on linguistic nationalism, the government retained religious symbolism in state practice and patronised Islamic institutions. They also recount disputes over religious sites, including expectations among Hindus that the historic Ramna Kali Bari temple would be rebuilt after the war.

More significantly, the book turns to politics. In 1975, Mujib introduced BAKSAL — the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League — a constitutional amendment that effectively created a one-party state. Other political parties were outlawed.

The authors describe it as “an attack on multiparty democracy” that is seldom discussed because it was followed quickly by his assassination in August 1975.

Here lies the book’s central contention: Mujib may have been the founder of the nation, but he was also a ruler confronting chaos, famine and rebellion, and his response included centralising power.

Myth-making and national necessity

Why, then, is Mujib remembered almost exclusively as a democratic secular icon?

The book’s answer is political rather than personal. Every nation requires a moral founding figure. Bangladesh, born through war and mass violence, needed a unifying symbol to stabilise its identity. Mujib became that symbol.

In this reading, memory is selective. The liberation leader is foregrounded; the party organiser of the 1940s and the centralising president of 1975 recede into the background.

This pattern is not uniquely Bangladeshi. India emphasises Gandhi’s moral leadership more than Congress’s internal conflicts. Pakistan highlights Jinnah’s constitutional vision while often downplaying the complexities of Partition politics. Founders become simplified because nations require clarity.

Why the debate matters now

The debate is not really about judging Mujib. It is about how states remember themselves.

Bangladesh today faces competing political visions — secular nationalism, religious identity, and electoral legitimacy. Each invokes Mujib. Supporters cite his pluralism; critics cite his concentration of power. Both sides appeal to the same figure because founders provide legitimacy.

That is precisely why historical re-examinations generate controversy. They do not merely reinterpret a man; they question a national story.

The book ultimately raises a difficult but necessary question: can a nation honour its founder while also accepting his contradictions?

A mature political culture, historians often argue, does not weaken by acknowledging complexity. It strengthens. Founders need not be flawless to be foundational.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remains the central figure in Bangladesh’s birth. But as Inshallah Bangladesh suggests, he was also a politician shaped by his era — colonial upheaval, communal mobilisation, war, famine and state-building.

Perhaps the real issue is not whether Mujib was saint or strategist, secularist or strongman. It is whether modern states can remember their origins without turning history into reverence.

Because the moment a founding father becomes untouchable, history stops being inquiry and becomes faith.