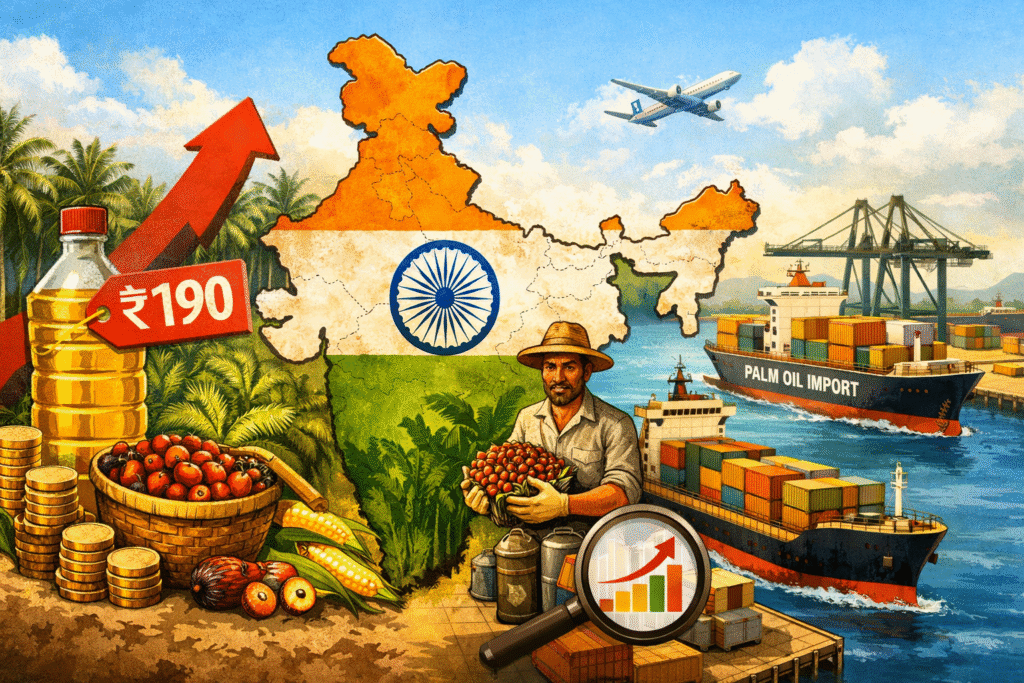

In mid-2021, as the Covid-19 pandemic strained lives and livelihoods, another quiet crisis unfolded in Indian kitchens. The price of cooking oil — a staple in nearly every household — surged by almost 50 per cent in a year.

A litre that once cost ₹130 now demanded ₹190. The shock was triggered not within India, but across plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia, where lockdowns hit a labour-intensive palm oil sector dependent on migrant workers. For India, which imports nearly 57 per cent of its palm oil, the disruption meant soaring prices, tighter household budgets, and a stark reminder of its vulnerability.

Edible oils are the second-most critical crop group in India after foodgrains. About 90 per cent of India’s 8.5 million tonnes of palm oil consumption is food-related. Yet domestic production still lags far behind demand.

In 2021–22, India produced around 116 lakh tonnes of edible oil while consuming more than 250 lakh tonnes. Unsurprisingly, India today remains the world’s largest edible oil importer and the second-largest consumer of palm oil after Indonesia.

In 2023–24 alone, vegetable oil imports cost India around ₹1.23 lakh crore — roughly 0.4 per cent of GDP, comparable to expenditure on core social sectors like health and education. This is not just a market statistic; it is a structural vulnerability.

India’s palm oil consumption is likely to mirror economist Walt Rostow’s stages of growth — modest consumption at early development, rising sharply with industrialisation and urbanisation, and eventually stabilising as incomes rise and diets diversify. But for now, the import bill is heavy, and the demand pressure cannot be wished away.

Recognising this dependence, the government launched the National Mission on Edible Oils–Oil Palm (NMEO-OP) in August 2021. The aim is ambitious: reduce import reliance by boosting domestic palm oil cultivation, particularly in the North-East and Andaman & Nicobar Islands, while expanding processing capacity and supporting farmers through subsidies and infrastructure.

However, achieving true resilience requires much more than planting more trees.

Palm fruits must be processed within 24–48 hours of harvest — yet India lacks adequate local mills and logistical infrastructure. Strengthening rural roads, ensuring faster transportation, and building decentralised processing hubs are critical. So too is improving yields through stronger R&D and better planting material. Palm oil is water-intensive; India’s short monsoon windows make sustainable irrigation systems, such as drip irrigation, essential.

Most importantly, smallholders must be at the centre of this transformation. Globally, they form the backbone of palm cultivation — and India is no exception. Fair pricing, assured procurement, training, and easier access to credit can make palm oil cultivation economically viable for farmers.

Palm offers one of the highest oil yields per acre, promising stronger and more stable rural incomes. But without adequate extension services, technological support, financing, and logistics, progress will remain slow.

Here, Thailand’s experience is instructive. Once heavily import-dependent in the 1980s, Thailand empowered independent farmers, promoted cooperative milling models, expanded credit access, and strengthened local processing ecosystems.

Today, it is the world’s third-largest palm oil producer, with India as its top export market. Learning from this approach — through decentralised processing, farmer-centric policies, public-private partnerships, and guaranteed buy-back frameworks — could help India build a more inclusive and resilient sector.

India now stands at a crossroads between an import-dependent present and a self-reliant future. Strengthening supply chains, investing in infrastructure, learning from Southeast Asian experiences, and ensuring fair trade partnerships will determine whether the palm oil mission succeeds.

As the economy grows and consumption patterns mature, palm oil demand will eventually stabilise. When that happens, India’s challenge will shift — from scrambling to secure supplies to shaping its strategic position in global edible oil markets. That means deeper South–South cooperation, sustainable expansion at home, long-term partnerships abroad, and ensuring growth that does not compromise environmental responsibility.

Self-sufficiency, then, is not isolation. It lies in building strength through smart interdependence — creating a palm oil ecosystem that is resilient domestically, competitive globally, fair to farmers, and sustainable for the future.